Rating: 8/10

Forgive me for getting a little pretentious here, but please bear with me on this roundabout tangent.

The Evolution of Storytelling

I've always been fascinated by anthropology, despite having only a layman's understanding of it. While I don't actively study human evolution or history, books like Sapiens and theories like Audio-Visual Intimidation Display really capture my imagination.

There's a particularly interesting set of theories about the evolution of myths, legends, and folk tales that explain them as products of "false positive cognitive bias"—our tendency to ascribe agency to observed events. Stewart Elliott Guthrie explores this in Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion, arguing that humans evolved to attribute desires, personalities, and goals to inanimate things because doing so was advantageous to survival. This, he theorizes, is why so many ancient myths personify natural phenomena. Lacking explanations for such events, ancient peoples reasoned they must be caused by someone, not something.

Greek mythology exemplifies this pattern, with gods like Poseidon and Zeus personifying the sea and lightning. In Norse paganism, even Ragnarök—the end and rebirth of the world—isn't caused by natural cycles of decay but by a cast of characters (Fenrir, Jörmungandr, Hrym) who personify that decay. In Egyptian and other mythologies, even primordial chaos has a personality and name. We're so inclined to anthropomorphize nature that we gave nothingness itself an identity.

Horror stories have always incorporated elements of this tendency. First came demons and devils. Then, as modern literature and film evolved alongside changing thoughts about nature and reality, people became interested in a wider variety of central conflicts: Man vs. Nature, Man vs. God, Man vs. Man, Man vs. Self—the classifications we all learned in high school.

The Modern Turn Away from Myth

Today's most popular media largely shies away from this older mythological style, where evil is personified as an entity that is simultaneously physical and abstractly powerful. Such stories still exist, but they're no longer as culturally dominant. We live in an age of science, and viewing the world through a religious lens feels rather outmoded. Consider some contemporary favorites:

Man vs. Nature: In The Expanse and Interstellar, a central conflict is the cruel indifference of space, which doesn't want to hurt humanity, it simply does. In Alien and The Thing, the threat is an intelligent alien with agency but no personality. Crucially, the human characters aren't completely helpless. There are rules to the game; the aliens are strong but not all-powerful.

Man vs. Technology: In The Terminator and The Matrix series, the antagonists are machines with agency and personalities, but they exist within a reality with rules. The machines face physical constraints on what they can and cannot do. No matter how powerful they are, the human cast can fight them and the human audience can understand them.

Man vs. Man: In Severance and The Boys, the main enemy is society and capitalism itself. While individual characters have agency, their actions exist within and because of their societal framework. Evil is the result of a faceless system. One might argue Homelander personifies societal ills in The Boys, but even he can't do it alone.

Man vs. God: Even novels like the Percy Jackson series, which incorporate Greek mythology, do so in ways that feel distinctly modern. The gods exist within a set of rules more akin to powerful wizardry than unknowable, awesome power. I realize this is opinion rather than argument, but to me, Percy Jackson feels closer to Harry Potter than to actual Greek myth.

Man vs. The Supernatural: Even the last horror movie I watched, Weapons, starts as a mystery with supernatural elements but ultimately reveals that the horrifying events fit within a fairly neat system. Again, there are rules—you don't have to believe in something supernatural if you can control and understand it.

These are all good stories, but they're distinctly modern in that they don't require belief from the audience. They weren't created by societies who, lacking other explanations for their struggles, turned to religion. In short, they don't feel like myths.

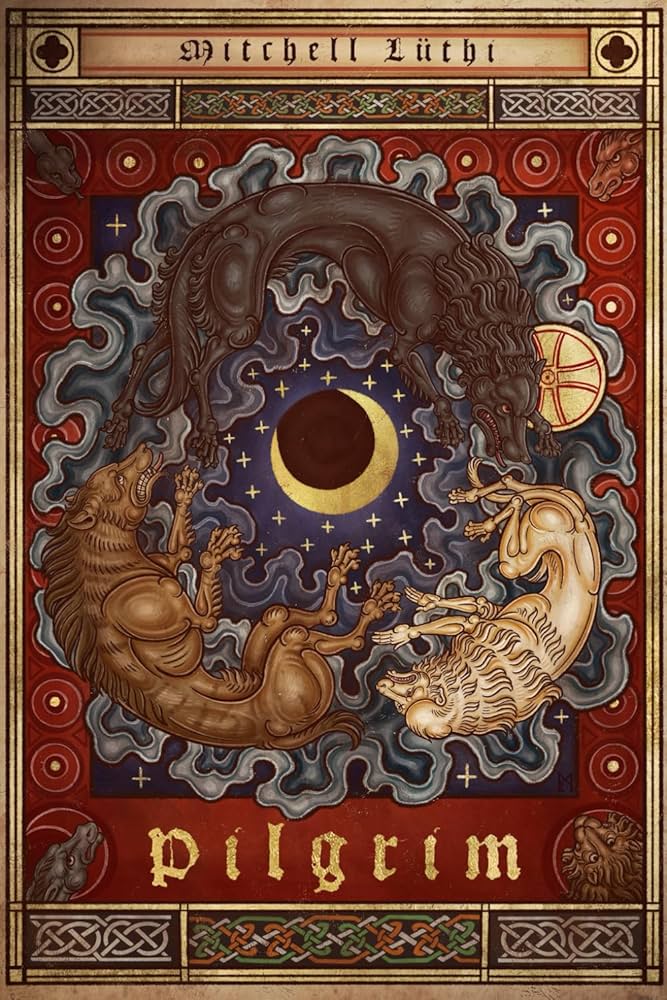

Enter Pilgrim

Pilgrim, by Mitchell Lüthi, feels like a modern novel that takes true inspiration from pre-modern myths. It blends conflicts of many different types into a mix that feels distinctly mythological. Audible described it as a "medieval horror story," which fits perfectly.

Have you ever read mythology and thought, "That doesn't really make any sense?" Like, supposedly Odin and his kin killed Ymir and fashioned the world from his corpse—but how? How did his bones transform into mountains and his blood into the sea? Where were these very real beings made of matter fighting if nothing physical existed yet? The conundrum exists because you're not supposed to question the story, but to believe in it.

If you've ever had that feeling, you'll experience it reading Pilgrim. Evil and good exist beyond human comprehension in a way that borders on nonsensical. Characters travel between the planes of hell without knowing how or why. Relics heal or wound without explanation. The monsters inhabiting the planes of Jahannam are intelligent, but their motivations remain unclear. The characters are mystified because the audience is supposed to be mystified—not knowing is scarier than knowing. There are explanations, but they make no sense, and the characters themselves comment on how little they understand. There's even less they can do about it except run and hope not to die.

In short, there are no rules to the game.

At the same time, the book is introspective and full of modern sensibilities. We spend much of it immersed in characters' internal monologues, with commentary on war and society that would resonate more with someone in the 21st century than the 10th. This meta-commentary gives the book a contemporary feel that ancient tales lack.

The prose feels distinctly medieval yet remains accessible. The horror evokes genuine dread and only devolves into cheap jumpscare-style gore in one or two scenes. The characters feel authentic, and most are quite likeable and engaging. As a reader, you must accept that you're not supposed to understand the mythological happenings—just go along for the ride, biting your nails all the way.

Final Thoughts

I loved Pilgrim because it feels both modern and ancient. The closest comparison I can make is that it reads like an H.P. Lovecraft novel minus all the science fiction elements—pure cosmic horror rooted in incomprehensible evil rather than alien technology.

My only complaint: the beginning feels a bit slow. But once the action picks up, it really accelerates, and the overall length is satisfying—neither too long nor too short.

Recommendation: I'd recommend Pilgrim to anyone interested in historical fiction, especially with elements of religion or horror. If you've ever wanted to experience what a true myth might feel like as modern literature, this is your book.